The Persian Concert Party 1909

February 3, 2021

Home News

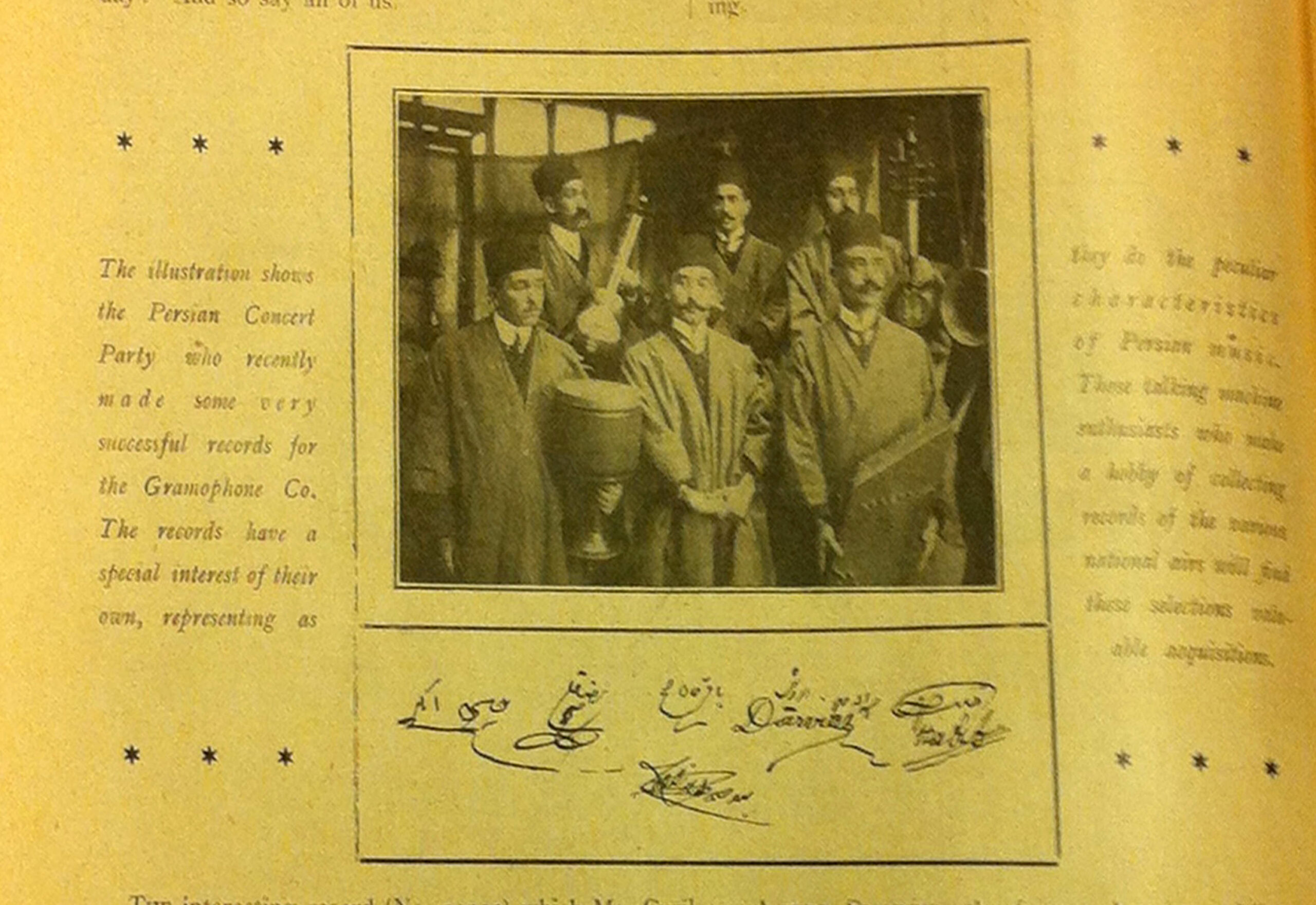

The Persian Concert Party

A story of musical collaboration between Persia and London in 1909

A story of musical collaboration between Persia and London in 1909

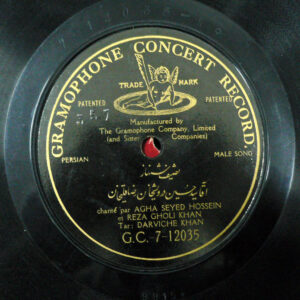

A group of the most eminent Persian musicians came to London in 1909 to make recordings for the Gramophone Company. The recordings they made on this trip remain some of the most important examples of Persian music of late Qajar period.

In Persia, from the late 19th century onwards, the Persian royal court demonstrated great interest in the technological advances of the West, especially from the time of Nasir al-Din Shah’s (reg.

1848-1896) three visits to Europe in 1873, 1878 and 1889. The Shah himself was a keen photographer. His son and successor Muzaffar al-Din Shah (reg. 1896-1907) was an enthusiastic amateur filmmaker and, like his father, travelled to Europe three times. His interests also extended to sound recordings of what later came to be known as the gramophone, or ‘talking machine’ as it was then called, so that by the turn of the century the Shah had already acquired several types of ‘talking machines’

1848-1896) three visits to Europe in 1873, 1878 and 1889. The Shah himself was a keen photographer. His son and successor Muzaffar al-Din Shah (reg. 1896-1907) was an enthusiastic amateur filmmaker and, like his father, travelled to Europe three times. His interests also extended to sound recordings of what later came to be known as the gramophone, or ‘talking machine’ as it was then called, so that by the turn of the century the Shah had already acquired several types of ‘talking machines’

Insofar as the Gramophone Company was keen to expand into the Persian market, in the winter of 1906, the company sent technicians to Tehran to record Persian music. General Lemaire, the director of the school of military music at the Polytechnic Academy (Dar al-Fonun), was charged both with providing the company with musicians from the Shah’s own orchestra and soliciting other eminent musicians in Tehran. Approximately 200 recordings were made at the Polytechnic’s Music College. Five recordings of Muzaffar al-Din Shah’s voice were made, in one of which the Shah can be heard praising the gramophone over all other ‘talking machines’. In February of the same year, the Gramophone Company was granted a royal warrant by the Shah to conduct business in Iran; they opened a branch in Tehran, with Mr Emerson as its director. The Persian imperial ‘Lion and Sun’ emblem was seen displayed proudly on all the marketing catalogues and advertisements of the Gramophone Company from this time onwards.

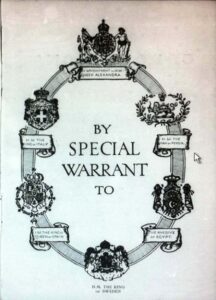

The Gramophone Company’s Tehran branch rented rooms in the famous Pharos building on Lalehzar Street, the most fashionable district of the capital. However, their business operation was not destined to last long. Mr Emerson arrived in Tehran to open up their branch during the middle of the Iranian Constitutional Revolution, which caused serious disturbances and disruptions to their business operations. The Bazaar was frequently closed; there were regular demonstrations, sit-ins and a general lack of security throughout the city. In 1907, on his deathbed, Muzaffar al-Din Shah finally gave in to the

The Gramophone Company’s Tehran branch rented rooms in the famous Pharos building on Lalehzar Street, the most fashionable district of the capital. However, their business operation was not destined to last long. Mr Emerson arrived in Tehran to open up their branch during the middle of the Iranian Constitutional Revolution, which caused serious disturbances and disruptions to their business operations. The Bazaar was frequently closed; there were regular demonstrations, sit-ins and a general lack of security throughout the city. In 1907, on his deathbed, Muzaffar al-Din Shah finally gave in to the

constitutionalists’ demands and granted Persia its own elected Parliament and constitution.

However, his successor Muhammad ‘Ali Shah (reg. 1907-1909) did everything he could to reverse the constitutionalists’ successes: he imprisoned activists, executed and exiled dissidents and prominent constitutionalists, fired cannons at the constitutional assembly building and bombarded the homes of prominent constitutionalist sympathisers. Around the same time, the Russians and the British partitioned Persia into respective spheres of influence: the north of the country fell under Russian ‘protection’, the south under British ‘control’, while central Persia – including Tehran was considered ‘neutral’.

All this upheaval brought the economy to a virtual standstill. Examination of the Gramophone Company’s correspondence from the period reveals that their sales did not meet their economic expectations and therefore could neither justify the costs of Mr Emerson’s salary nor the maintenance of an independent Tehran branch. Accordingly, Mr

Emerson and his family left Iran in the fall autumn of 1908. A two-year contract for distribution and sales of the Gramophone Company’s remaining stock was signed with Hambartzoum Hairapetian & Cie [sic], Armenian merchants based in Persia, on a commission basis in the autumnfall of 1908.

Emerson and his family left Iran in the fall autumn of 1908. A two-year contract for distribution and sales of the Gramophone Company’s remaining stock was signed with Hambartzoum Hairapetian & Cie [sic], Armenian merchants based in Persia, on a commission basis in the autumnfall of 1908.

Hambartzoum was keen to increase the variety and quantity of their stock but London Gramophone Company was understandably not keen on sending any of their own engineers to Tehran for recording. Mr Hambartzoum thus arranged to send Persian musicians to London to make recordings; he made all the arrangements for their trip and accompanied the musicians, acting as their guide and translator, offering them very generous remuneration for their trip and recordings.

Eight of the most distinguished Persian musicians of the day were invited to go to London. Six of them were members of the Anjoman-e Ukhuwwat (Society of Brotherhood), a branch of the Ni‘matullahi Sufi Order headed by Zahir al-Dawla, a prominent constitutionalist. Zahir al-Dawla’s house, along with the Anjoman-e Ukhuwwat’s meeting hall, had been bombarded and ransacked by royalist forces about the same time the parliament building was bombarded. These musicians included legendary names such as: Darvish Khan (tar), Hang Afarin (violin), Bagher Khan (kamancheh), Mirza Asadu’llah (tar, santur), Habibu’llah Shahrdar (piano), Tahir-zadeh (vocals), who all performed regularly in the concerts held in the garden of Zahir al-Dawla’s home and in the meeting hall of the Anjoman-e Ukhuwwat in support of the constitutionalists’ demands. The other two members of the group: Akbar Khan (flute), the younger brother of Hang Afarin, and Reza Quli Khan (vocals and zarb), although not members of the Anjoman, were close friends with the others.

The group embarked from Tehran in mid-February 1909, heading north toward the Caspian port of Anzali. The north was under the control of the pro-constitutionalist fighters (Mojahhidin). They reached the river bridge of the town of Manzil on the road to Rasht before the fighters destroyed it on 17 February, where they were stopped by constitutionalist forces who demanded that Darvish Khan play for them for half an hour before proceeding. Again, when they reached Rasht, they were stopped and only allowed to continue on their journey once they agreed to give a three-day benefit concert for the Mojahhidin.

Exiting Persia, they travelled through Russia to Europe, eventually reaching London in April 1909. The group’s recording sessions took place at the Gramophone Company studio on 21 City Road in London from 12 to 23 April. During these eleven days, the group made over 300 recordings, the records from which were pressed at the London Hayes and Russian Riga factories, and

marketed in Iran and internationally. Today these recordings constitute some of the few examples of what Qajar music sounded like. It has been rumoured that the Persian musicians also performed at the Imperial White City International Exhibition (held during June) whilst in London. However, this is unlikely because no notice or review of them performing any public concerts in London appears in any contemporary publications or the exhibition catalogues.

marketed in Iran and internationally. Today these recordings constitute some of the few examples of what Qajar music sounded like. It has been rumoured that the Persian musicians also performed at the Imperial White City International Exhibition (held during June) whilst in London. However, this is unlikely because no notice or review of them performing any public concerts in London appears in any contemporary publications or the exhibition catalogues.

In sum, the recordings of Persian music made by the British Gramophone Company – later to be called His Master’s Voice – in collaboration with Persian musicians during the late 19th and early 20th centuries today remain one of the most significant resources and documents for the history of Persian music.

Jane Lewisohn is a Research Associate at the Music Department of SOAS, Director of the Golha Project (www.golha.co.uk) and of Golistan: a Virtual Museum for the Performing Arts of Twentieth-century Iran (www.golistan.org)